Lithuanian alphabet

-

by sabaliukena

- August 31, 2023

- 5:41 pm

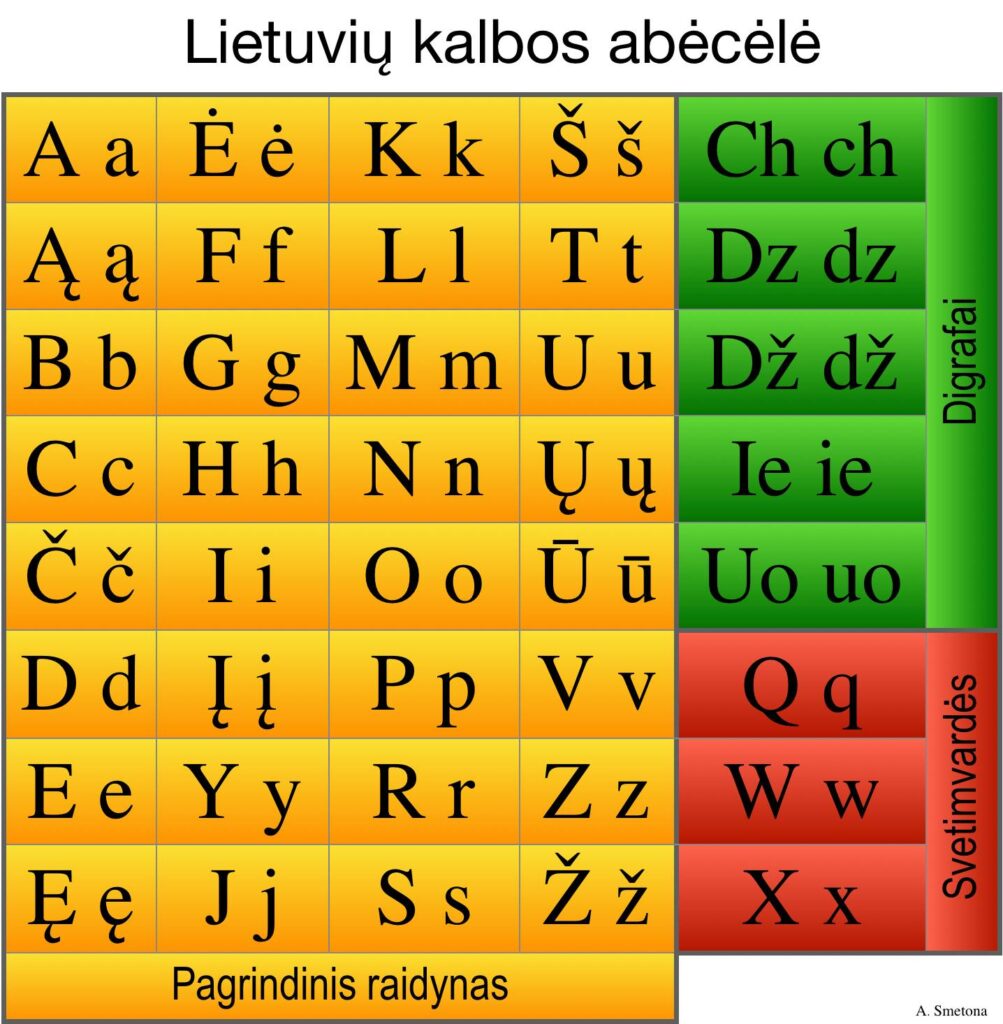

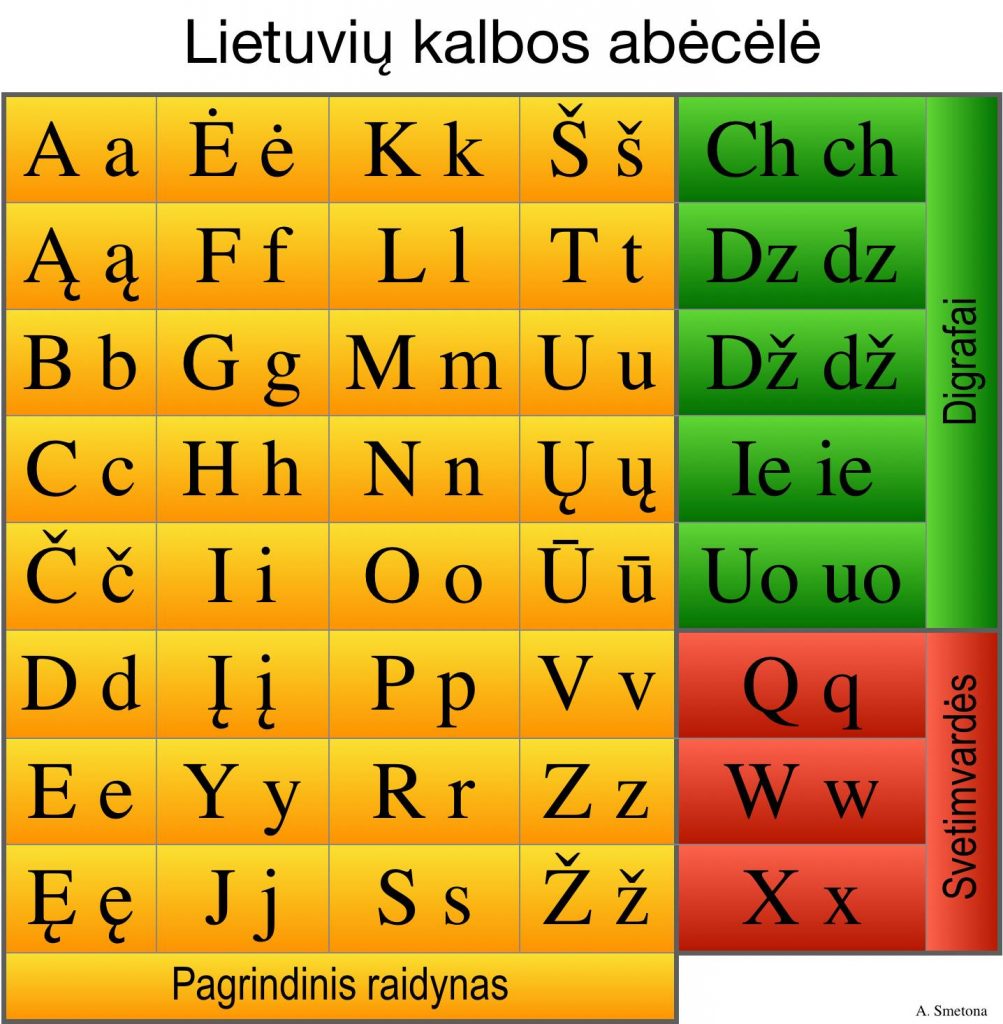

The standard Lithuanian alphabet consists of 32 letters:

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| A and | a | [ɐ], [ɑː] |

| Ą ą | a handkerchief | [ɑː] |

| B b | be | [b], [bʲ] |

| C c | See | [t͡s], [t͡sʲ] |

| N N | See | [t͡ʃ], [t͡ɕ] |

| D d d | thanks to | [d], [dʲ] |

| E e | e | [ɛ], [e], [ɛː], [æː] |

| Ę ę | e handkerchief | [ɛː], [æː] |

| Ė Ė | ė | [eː] |

| F f | ef | [f], [fʲ] |

| G g | gay | [g], [ɡʲ] |

| H h | ha | [ɣ], [ɣʲ] |

| I and | i short | [ɪ], softness sign |

| To the | i handkerchief | [iː] |

| Y y | i long | [iː] |

| J j | jot | [j] |

| K k | that | [k], [kʲ] |

| L l | [l], [lʲ] | |

| M m | em | [m], [mʲ] |

| N n | en | [n], [nʲ], [ŋ], [ŋʲ] |

| About | o | [ɔ], [oː] |

| P p | See | [p], [pʲ] |

| R r | er | [r], [rʲ] |

| S s | I | [s], [sʲ] |

| Š Š | See | [ʃ], [ɕ] |

| T t | tė | [t], [tʲ] |

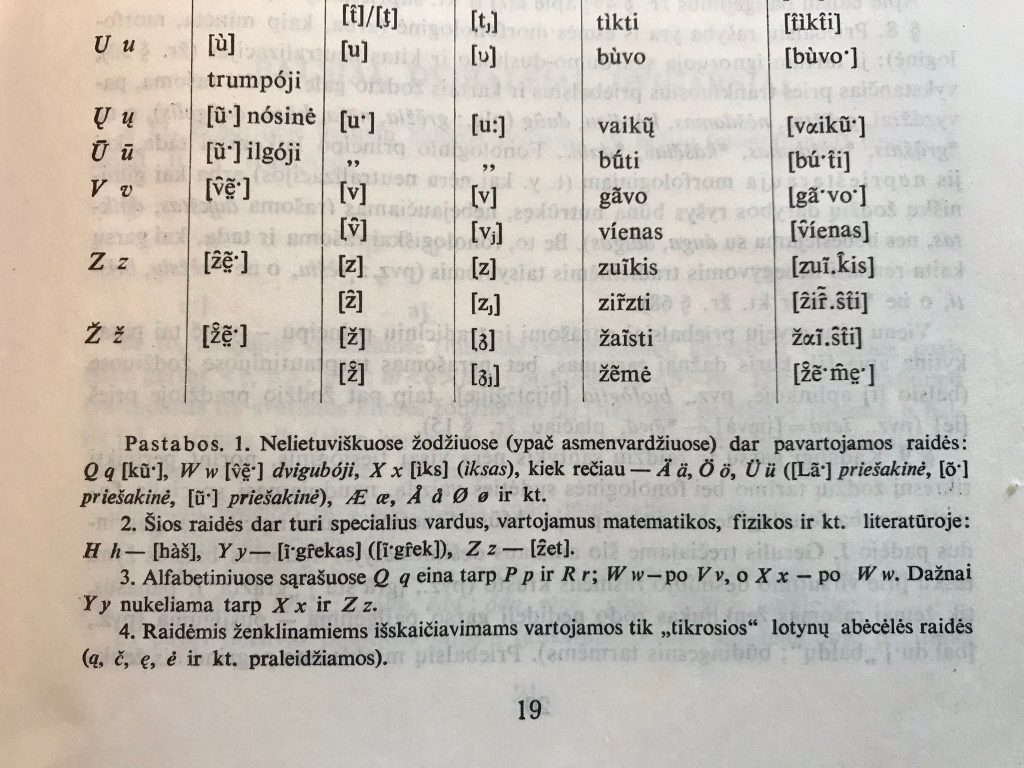

| U u | u short | [ʊ] |

| Ų Ų | U handkerchief | [uː] |

| Ū Ū | u long | [uː] |

| V in | cancer | [v], [vʲ] |

| Z z z | zé | [z], [zʲ] |

| Ž Ž Ž | See | [ʒ], [ʑ] |

The remaining three letters of the Latin alphabet can be used for foreign names:

| Letter | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Q q | kū | [ku], [kuː] |

| W in | double crayfish | [v], [vʲ] |

| X x | ix | [ks], [ksʲ] |

Remark: In alphabetical lists Q q goes after P p, W w - after V v, X x - after W in.

A little history: The Lithuanian alphabet was first presented in the first known Lithuanian book, Martynas Mažvydas's Katekizmas (Catechism), in 1547, which contains 23 uppercase Latin letters and 25 lowercase letters. Of the Latin capital letters, the following are not mentioned j, u and w. There are also some oddities of the time: only the capital letters of the v, among the little ones appear u, v, and in the text of the book all three are used u, v, w. There were still none of today's usual ą, ę, ė, č, į, ų, ū, š, žwhich are actually the same Latin letters, but "enhanced" with diacritics.

Due to the Western cultural influences and the circumstances of the emergence of printed script at that time, the Gothic script became popular in Lithuanian writing at first, but from the end of the 18th century there was a massive shift to Renaissance antiquity. Although in some places (e.g. Lithuania Minor) the Gothic script remained popular until the early 20th century.

The lack of letters for specific Lithuanian sounds was immediately apparent, so in the 16th-19th centuries various authors and publishers experimented with improving the Lithuanian alphabet, both by creating it themselves and by adapting the experience of neighbouring nations. For example, ė Daniel Klein's Grammatica Litvanica appears for the first time. Š, ž, č originally written in German or Polish sz, sch, rz, cz, and in the late 19th century they were adopted from the Czech alphabet. Handkerchief letters ah, ah taken over from the Poles, and į and ų based on the same example. Same time and letter ū Jonas Jablonskis proposes the Lithuanian alphabet.

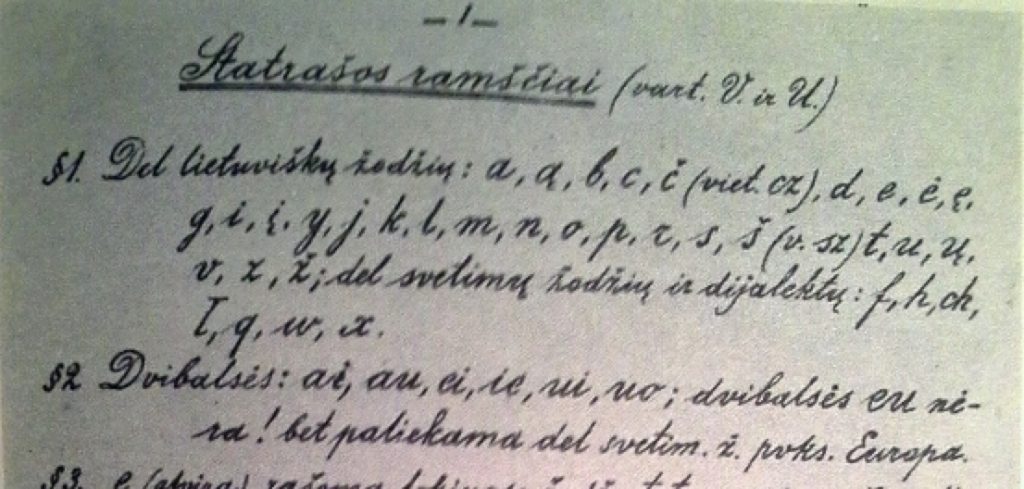

The Lithuanian alphabet took its almost modern form at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The pioneer of the modern alphabet is Vincas Kudirkas with his "Statraša ramščiai", 1890. It differs from the current alphabet only in two letters: there is no ū and no longer ł. True, f, h moved to the main alphabet, q, w, x continues to be used only to write foreign pronouns, and See is generally stuck between heaven and earth: it seems to have become suitable for writing adapted foreign words, but it has never entered the mainstream alphabet.

Three years later, Jonas Jablonskis proposes a letter ū in the articles "Dar keletą žodžių o mūsų pisybą" ("Varpas", 1893/1) and "Ar potrzebingi tamri znamklai ilgojom i and u express?" ("Varpas", 1893/8). In the first article, Jablonski talks about the problems of the Lithuanian alphabet and proposes his own version. At the same time, he proposes a letter ū and uses it consistently himself - namely, empty, be, maybe-maybe... It is true that Jablonski's alphabet differs much more from the modern one than in V. Kudirka's "Statrasha ramščiai" (e.g. Jablonski himself neither proposes nor uses the letter č). Therefore, the rumour that Jablonski will contribute to the "Pillars of Statrasha" can probably be refuted. I note that, like V. Kudirka, Jablonskis uses Latin letters to spell foreign words.

Despite all sorts of historical vicissitudes and disputes, the tradition of V. Kudirka and J. Jablonski has continued throughout the 20th century and has consistently reached our times. Without going into all the twists and turns and crossroads of more than a hundred years, it can be said that exactly the same things that Kudirka and Jablonski said are repeated in the "Present Lithuanian Language grammar" in 2006. Authors of the alphabet chapter Aleksas Girdenis and Kazimieras Garšva.

Letter to sound ratio: The Lithuanian alphabet is a relatively perfect representation of the sounds of the Lithuanian language. Although the Lithuanian spelling is based on three principles - phonetic, morphological and historical - the phonetic principle is predominant, i.e. we mostly write as we hear, and there are no complex combinations of historical signs in the standard Lithuanian spelling.

The spelling of consonants is very systematic - all consonants are spelled in one form, although as sounds they come in two forms - soft and hard (except jwhich is always soft). There are no regular signs for soft and hard consonants, as the positional softness/hardness of consonants is easily reproduced in standard speech: all consonants preceding back consonants are pronounced hard, and all consonants preceding front consonants are pronounced soft (e.g.: leaf - ice, dune - loop, fly - love); they are written in the same way, as we can see. There are a few cases where a consonant is softened before the back consonants, then the softness is indicated by the softness sign i (for example: folk - fire, miaukia - maukia, Brutus - brutus); the softness mark indicates no sound.

Morphological spelling is related to the consonantal loudness/loudness opposition. The guttural consonants before the voice consonants are contracted, while the voice consonants before the voice consonants are contracted. This leads to cases where we use a guttural consonant to mark a muffled sound and vice versa (e.g.: run [run], pop over to [to shake, to bounce], to be enslaved [ižžerkti, ižerkti]). For a native speaker of English, such inconsistencies in the spelling of consonants do not cause any problems in reading and understanding the text. On the contrary, it is difficult to write the dictated text correctly, because one needs to know which word forms to use to determine the actual (unassimilated) sound.

It may also be noted that one consonant does not have its own letter in the alphabet: the consonant [ x ], [ xʲ ]. This consonant is new to Lithuanian, having come with foreign words, and therefore only occurs in them. As can be seen from the tables above, the adapted foreign words use a digraph to write it Ch ch. The inclusion or exclusion of diphthongs for individual sounds in the main alphabet is a matter of tradition, e.g. the Czechs also have the same diphthong and include it in the alphabet, while the Poles, who have a much larger number of diphthongs and even triphthongs, do not include them in their alphabet. So here we are following the Polish tradition.

The main oppositions of vowels in Lithuanian are tonal - short/long and ascending/descending length, i.e. tone. There are three signs for vowel tone, which can be written above vowels or semivowels l, m, n, r. These are acute (descending longitude), circumflex (ascending longitude) and gravis (shortness) (e.g: káltas - kãsa - kasà, výras - grỹbas - vìsas). The use of tone marks is not a mandatory feature of standard spelling. It is more often used for teaching and scientific purposes or in cases of ambiguity, and natural speakers can easily produce tones without it.

The main spelling problem is the shortness/length of vowels. Length is both positional and historical. Different letters are provided for vowels of different lengths in Lithuanian, although the historical tradition is not entirely consistent. For example, the letters o, ė, y, ū always denotes long vowels. Letters u, i always indicates short vowels. The vowel is an exception to this owhich can be short in relatively new borrowings. Nevertheless, there is a clear trend towards longer o even in foreign words, which is why the word Dollar Votes o can actually be short, half-long or long. And this lengthening tendency is tolerable in standard speech. Nasal letters ą, ę, į, ų are used to denote nasal sounds that have long since disappeared in the language, i.e. historical length, e.g.: oak, bold, brave; lentil, kãtė; nósį; rańkai. Here we see nasal letters representing long sounds in the unstressed position in the root and ending of the word. Theoretically, they should all represent long vowels, but the reality is a little different - even historical sounds are getting shorter when they lose their stress in the root, and the shortening of long endings is almost epidemic. In letters a, e vowels are strong examples of positional length - they are usually long when accented and shortened when unstressed (there are exceptions in monosyllabic words), e.g: vãsara - summer, vẽda - marriage.

Addendum: Digraphs are also used to record some sounds. These are used to record one consonant, two affricates and two consonantal diphthongs: ch, dz, dž, ie, uo. These digraphs are distinguished because they are, by definition, already marking separate, single sounds. By the way, there are nine diphthongs in the Lithuanian language. The remaining seven are simple, non-contiguous digraphs, because their binomial sound structure is still very clear. Here are all the Lithuanian digraphs - one consonant, two affricates and nine diphthongs:

| Double sided | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Ch ch | cha | [x], [xʲ] |

| Dz Dz | See | [d͡z], [d͡zʲ] |

| Dj | See | [d͡ʒ], [d͡ʑ] |

| Ai ai | ai | [âˑɪ̯], [ɐɪ̯ˑ] |

| Ouch | au | [ âˑʊ̯ ], [ɐʊ̯ˑ] |

| Hey hey hey | ei | [æ̂ˑɪ̯], [ɛɪ̯ˑ] |

| Eu eu (iau) | eu | [ɛ̂ʊ̯], [æ̂ˑʊ̯], [ɛʊ̯ˑ] |

| Ie ie | See | [îə], [iə] |

| Oi oi | oi | [ɔ̂ɪ̯] |

| Oh oh oh | or | [ɔ̂ʊ̯] |

| Ui ui | ui | [ʊ̂ɪ̯], [ʊ̯ˑ] |

| Uo uo | oo | [ûə], [uə] |

Remark: In alphabetical lists, digraphs are in the order of their first letters.

All in all, it is possible to compile a general list of letters of the Lithuanian language, which really shows the true state of our alphabet, its hundred and thirty years of tradition, and maybe it would reduce silly disputes.

Source: https://www.smetona.lt/pastabos-parastese/lietuviu-kalbos-abecele/